Black Island

By J. Michael Cole

Black Island describes how the pivotal years 2013 and 2014 exposed the pitiful inadequacies in both the two-party structure of Taiwanese politics and the narratives we use to talk about Taiwan. These were the years when a new set of groups rose to prominence, unaffiliated with any political party, in response to the failures of Ma Ying-jeou’s second term.

The first and final thirds of this book are a narrative made up of opinion pieces published by Cole during this period. This narrative tells the story of grass-roots protests against acts of high-level overreach: plans by Chinese-sympathetic corporate behemoths to acquire Taiwanese news media, and the land expropriation scandals at Huaguang Community in Taipei and Dapu Village in Miaoli in 2013. These protests represented a blossoming of Taiwanese civil society’s confidence to make its voice heard against government actions it saw as cold-hearted, greedy, and/or lacking in transparency.

Cole makes it very clear that these protests cannot be made to fit into the standard ‘blue vs. green’ dichotomy traditionally used to make sense of Taiwanese politics; in the Huaguang Community land expropriation case, for instance, young student protesters (traditionally ‘green’ voters) championed the cause of elderly residents who had been born in China (the most stereotypically ‘blue’ people one could imagine).

Cole also demolishes the idea that these protesters were agents of the DPP in a proxy battle against the KMT, a framework used by some hack journalists and pundits to explain the increasingly tumultuous events of 2013 and 2014. Not only have the protesters kept a careful distance between themselves and the DPP, but Cole does not hesitate to point out how DPP officials have been duplicitous and hypocritical while promising to help the ‘little guy’. Where DPP officials failed to lead, public protests rose up.

The second part of the book is quite different from the first and third sections, as it deals with the gay marriage battle here. Taiwan is on the whole one of the more progressive countries in the non-Western world when it comes to LGBT issues. Social issues have not been politicized to the extent that they have in the USA (they don’t fit neatly into Taiwan’s traditional Blue v. Green political polarization) and while many families are still run under traditional lines (anecdotally, I’ve heard many gay Taiwanese are ‘out’ to their peers but not to their parents), there is little anti-gay sentiment in society at large. It is easy to be optimistic that same-sex marriage will become a legal reality in Taiwan soon, as polls show a majority of people either actively support legalization of gay marriage or are indifferent to it.

In this section, Cole examines the gay-marriage fight in Taiwan and the segment of society that seems most opposed to it: Christian church groups. According to Wikipedia, less than 5% of Taiwan’s people are Christian. However, Christian churches have been able to mobilize to the point that they pull significantly above their weight on this issue, despite the fact that there’s not much traditional anti-gay bias in Taiwanese culture. (Or in the teachings of Jesus, for that matter. Sure, there is anti-gay stuff in Leviticus and Deuteronomy, but as everyone who’s actually read them knows, most bible-thumpers have to cherry-pick liberally from those books.)

As Cole delves into the background of the Christian churches leading these anti-gay movements, he uncovers connections to the creepier side of American evangelical Christianity. Many of these connections involve the Bread of Life Church, which sent all sorts of weird feelings up and down my spine because I’ve walked right past this church’s Taipei location on Heping East Road countless times over the years.

All in all, this is a subject Cole feels strongly about: a very close family member of his is gay and married, so it's easy to understand his righteous anger at homophobic church groups peddling anti-gay slander as religion (not that he needed an excuse of course). As the subject matter is quite distinct from the first and third chapters, Chapter 2 does fit slightly awkwardly into Black Island as a whole, but I suppose one could see it as a dark side of the Taiwanese civil society whose awakening Cole celebrated in Chapter 1.

The final section of Black Island opens on the eve of the Sunflower Movement’s occupation of the Legislative Yuan on March 19, 2014.

For me personally, though I lived in Taiwan for the entire period of time covered by Cole’s book, I never really paid enough attention to the events covered in Chapter 1 while they were ongoing to fit them into a larger mental framework. I saw stories in the news about anti-government protests and worries about Chinese influence in Taiwanese media, but seldom gave them more than a passing notice. The Legislative Yuan occupation was very different though -- a real ‘holy crap, is this actually happening?’ shock delivered straight to my brain.

Unlike certain people whom I am married to, I never actually ventured to the vicinity of the Legislative Yuan while the occupation was going on to hang with the protesters. That said, I did go to the mass protest of March 30. While I don’t have the expertise to estimate numbers, I can say it felt like the largest gathering of human beings that I have ever personally witnessed, and I am easily inclined to believe the higher estimates of how many people actually came out that day.

I’ll admit that when the occupation began, I was antsy and nervous -- dudes, is this really a good idea? Will it really help your cause? Think about the optics, people!

In retrospect, I was wrong. The images left in people’s brains are ones of overwhelming civility -- protesters being kind to police, and occupiers cleaning the Legislative Yuan to make it nice before vacating it. Whatever you may think of their politics or their methods, the Sunflowers won the optics.

The short-lived Executive Yuan occupation of March 23 left a very different impression. I remember sitting on the couch at home that night, nervously watching a livestream of the events, wondering just what the people involved could possibly be thinking. Every time I heard a siren in the distance I assumed it was headed toward the Executive Yuan (and as I live in central Taipei, there’s a good chance I was right at least some of the time). And when I went out the following day, after police violently evicted the protesters, I felt as if there was a noticeable sense of dazed glumness hanging over the city -- a sense of ‘geez, what is this country coming to?’ (With that said, I must point out that in a country just a few decades removed from tyrannical military rule, the biggest police crackdown of the pivotal year of 2014 produced zero fatalities. This is, by global standards, an extremely civilized country. May it always stay that way.)

I am absolutely not defending the violence of the police crackdown at the Executive Yuan, but I never really warmed up to the protesters’ actions when occupying it -- a bit too much like prodding the beast to get a reaction. Fortunately, the aforementioned mass protest of March 30 took place a few days later, and helped cleanse the EY occupation’s bad taste from my mouth.

And it does feel as if the country has been different, post-Sunflower. It’s not just the two devastating KMT electoral losses; there’s also been a blow struck against the condescending old “we know what’s best for you, so sush your mouth and let the adults run things” mentality of the past. There was more reason to feel optimistic about Taiwan’s future at the end of 2014 than when the year started, and in the time since, my optimism has only grown.

In conclusion, Black Island is a better read than Officially Unofficial, because Cole is reporting and opining on events rather than writing a memoir, which means he spends far less time explaining and defending his own actions and far more time describing the political situation in Taiwan, which is presumably what the reader is more interested in. The essays that make up the book all deal with Cole’s two main topics, which means the reader will have to look elsewhere to find coverage of other issues in Taiwanese politics during this time, such as President Ma Ying-jeou’s attempts to oust Speaker Wang Jin-pyng in the autumn of 2013.

The fact that the book is a collection of previously published essays means that the prose has a certain amount of repetition, and of course this is a collection of opinion pieces, not a magisterial work of history. I note that no publisher’s name graces this book; there are several typos and malformed sentences that likely would not have gotten past a professional editor. Also, twice in the book the reader is presented with a paragraph of Chinese text, for which no English translation or gloss is given, but the reader is still apparently expected to read and understand. (I choose to view this not as an oversight, but rather as a vote of confidence in my language ability.) If you’re on board with these issues, Black Island is an excellent look back at several interesting aspects of the last few years of Taiwanese political history.

My own views don’t always match up exactly with Cole’s. I think I am more of a free-speech absolutist than he is. In the Chapter 2, when Cole spoke of anti-gay groups that defended themselves by saying they had freedom of speech to speak their mind, I wish he had pointed out yes, these groups do indeed have a right to free speech, but asserting it’s not illegal to state your opinion is literally the weakest possible argument in favor of your opinion that you can make. Also, Cole’s tendency toward pomposity, while less pronounced here as in Officially Unofficial, still pops up from time to time; see the occasional overblown metaphor and his silly cliched rant about smartphones at the opening of Chapter 3.

In the end, the lessons learned from Black Island can be applied beyond the shores of Taiwan. Of course in many ways Taiwan is unique -- most countries do not have an enormous neighbor threatening annexation or war. But Taiwan is not the only country with an ostensibly democratic government that acts like an authoritarian regime when convenient. Cole describes how Taiwanese civil society is capable of spawning groups that can exert pressure on governments, independent of established political actors. This lesson applies outside Taiwan, and it will keep governments around the world on their toes in the coming years.

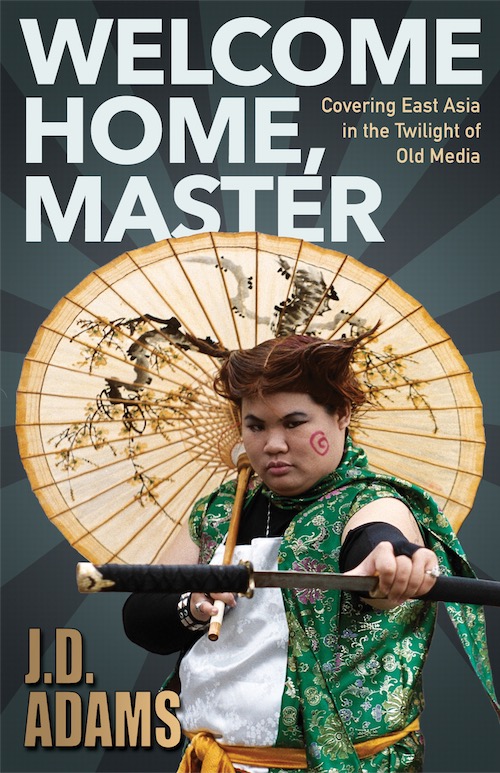

Welcome Home, Master: Covering East Asia in the Twilight of Old Media

Welcome Home, Master: Covering East Asia in the Twilight of Old Media