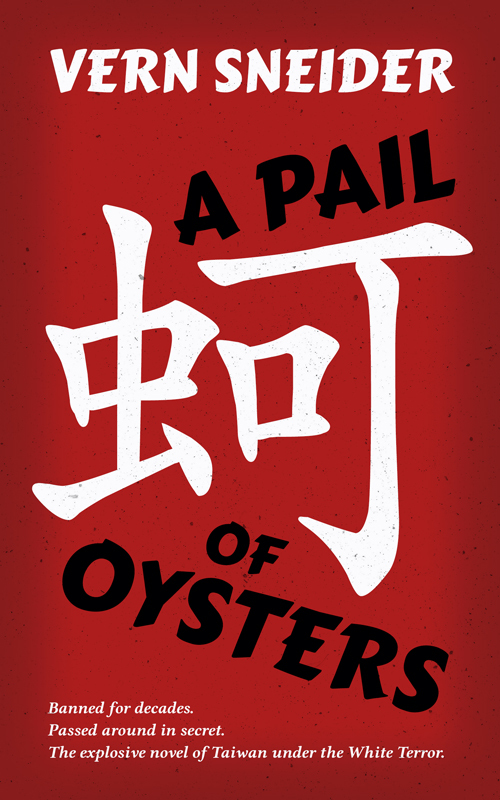

by Vern Sneider

In 1953, American journalist Vern Sneider published his novel A Pail of Oysters to acquaint Western readers with the political situation in Taiwan. The ROC had come to Formosa less than a decade before, and the West saw it as a bulwark against Communism that must be supported with financial and military aid. Sneider did not write his book to bring us Chiang Kai-shek’s side of the story; he sides with the ordinary people of Taiwan who suffered under ROC rule, the White Terror, and the after-effects of the 228 Incident.

The story begins by introducing us to Aboriginal youth Li Liu, his family, and their daily struggle for existence, harvesting oysters from the coastline and trading them for rice and other necessities. Not a prosperous family even in peaceful times, their daily life is made harder by the bands of ROC soldiers (called ‘Save-the-Country soldiers’) who see it as their right to loot at will from these unimportant nobodies. When the family’s god-image is stolen, Li Liu sets off to recover it. On his adventure he meets friendly American (and obvious author surrogate) Ralph Barton, hardscrabble former prostitute Precious Jade, and Precious Jade’s brother, who goes by no name because he no longer acknowledges his tyrannical adoptive father.

The story that follows is a fairly simple one, all things considered, with a couple of big narrative coincidences that make it seem like the population of Taipei is maybe a hundred people. It is not hard to predict our heroes are not going to have a happy ending, even as the narrative teases us and makes it seem things might actually work out well for them. You know they’re not going to have a happy ending because the book’s purpose is to make people outraged. That’s not a bad thing, because sometimes outrage is warranted.

This novel is meant to raise political awareness, using the novelist’s timeless tool of taking impersonal numbers from news accounts (‘thousands executed in anti-Communist purges’) and turning the statistics back into tragedy by giving a small handful of them individual names, backstories and personalities. The number of verifiably Communist characters in A Pail of Oysters is zero, but we see how anti-Communist witch hunts can be a very useful tool for unscrupulous people pursuing their own personal vendettas that have nothing to do with politics. The book is also an interesting historical perspective on issues that, 64 years later, are still controversial and unresolved, notably expropriation of land owned by local farmers.

The book turns didactic midway through when a Taiwanese businessman with dissident sympathies, Mr. Chou, turns up to lecture Ralph Barton about what should be done for Taiwan, and by doing so crowds two of the three Taiwanese viewpoint characters out of the narrative for a large chunk of the book. Mr. Chou, whose views are never rebutted and so are presumably Sneider’s own, thinks the KMT shouldn’t be removed from power entirely, but rather sees a pro-democracy faction within the KMT that ought to be running the country rather than the authoritarians in power instead. (Presumably he's thinking of K. C. Wu and the liberal faction he represented. It's too bad that, at about the same time A Pail of Oysters was published, Wu went into permanent exile in the United States.)

One could argue that Sneider is fairly diplomatic towards the KMT/ROC, all things considered. He makes an effort not to paint ROC soldiers as uniformly evil, and Chiang Kai-shek himself is never directly criticized. Chen Yi, the military governor of Taiwan in the immediate postwar years, is the one real-life figure who does get thoroughly blamed by name in the text. Again, Sneider’s being diplomatic here -- by the time the book was written, the KMT had already removed Chen from power and executed him.

Sneider may have tried to be diplomatic, but it appears the KMT did not appreciate his helpful suggestions. The novel was banned in Taiwan, and according to the Taipei Times, rumor has it that pro-KMT students hunted down copies of it in libraries overseas and burned them (since that’s how you look like the ideological good guys, you know). The American political climate in the 1950s was not very receptive to the novel’s themes of “anti-Communist witch hunts hurt innocent people” and “the KMT is not always good” and so the book's success failed to live up to its author’s hopes.

To be honest, A Pail of Oysters is not great literature. But that doesn't mean it's not worth reading. Now that it’s available again from Camphor Press in e-book or paper form, it’s of great interest for anyone invested in Taiwan. A comparatively thin volume (I read it on a Kindle and was surprised at how fast the %-completed figure rose), it gives a fascinating historical perspective on Taiwanese history and politics as perceived by a Westerner in the 1950s.